Hannah Amuka

How can quilts made by Black women change the way we tell the history of abstract art?

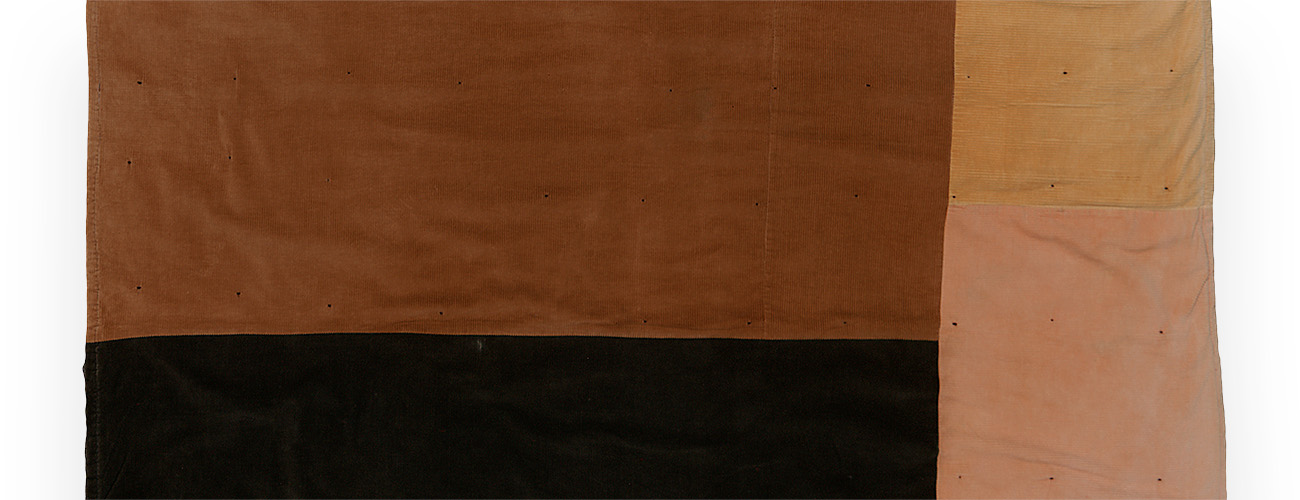

China Pettway (American, born 1952), Blocks (detail), 1975, corduroy and cotton hopsacking, 83 × 70 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, museum purchase and gift of the Souls Grown Deep Foundation from the William S. Arnett Collection, 2017.68. © China Pettway/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Abstraction and its various painterly expressions—like Piet Mondrian’s paring down of nature to its essential form through his grid-like paintings of the early 1900s—has historically liberated traditions in the art academies from solely privileging naturalism to freeing painting from form.1 In the subsequent decades when the American art scene shifted its lens toward a national consciousness, Harlem emerged as the epicenter for the exploration of Black Abstract Expressionism, as artists such as Aaron Douglas and Samuel Joseph Brown Jr. added to the evolution of these painterly languages. Still, while various modes of Black abstract art gained widespread appreciation, most notably the expressive sounds and lyrical constructions of blues and jazz, Black women craftworkers remained on the outskirts of mainstream art appreciation.

Perhaps the reason quilts by Black makers have not been considered fine art masterworks is the way the circumstances of their production and the lived experiences of their makers tell truths about American history. Or as stated by Bridget R. Cooks in Exhibiting Blackness: African Americans and the American Art Museum, the work of women from rural isolated communities like Gee’s Bend “[transgresses] normalized boundaries of class, race, and elitist investments in high versus low art.”2

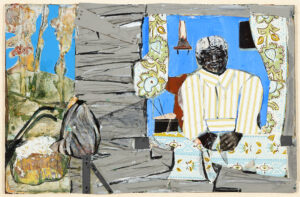

It’s from this understanding that we can begin to examine the myriad ways quilts made by Black women offer museums a pathway to telling richer and more expansive histories of abstract art. As Cuesta Benberry notes in Always There: The African-American Presence in American Quilts, African Americans have made quilts in this country continuously from the late 1700s to present day.3 This tradition mirrors the central role textiles play in continental African communities, to which craftsmanship and techniques used in fabric construction are highly regarded and a rich system of symbols are woven into cultural craft objects. It should come as no surprise, then, that across the Atlantic, Black American quilt makers continued this rich tradition of piecing cloth together to embed oral histories into the bedcovers that sheltered their families from the cold. Though revered twenty-first century artists like Romare Bearden and Radcliffe Bailey often paid homage to Black Southern quilters in their work, the exclusion of women from the discourse of mastery in cultural institutions remains. Dated three years before Bearden’s death and well into his prestige as a fine artist, Lady and Quilt (fig. 1) honors the rural Southern communities of his roots and places both the women makers and their craft at center. The open corner at lower left of the frame depicts a bale of cotton, hinting to the rural labor and legacy of servitude to the land.

The onus is on museums and art scholars looking to adopt more inclusive practices to recognize the long-held criteria and principles used to qualify artistic genius as uniquely demonstrated in quilts. Though a mastery of technical skill and an understanding of balance and harmony in the formal elements are present, it’s important to note that these textiles were made to be used by loved ones and served as forms of resistance and often meditations on grief. Placing the creative expression and ingenuity of Black domestic craftwork into the fine art space as abstract art allows for more robust and critical conversations around the genre, but only if the materials retain their origin story.

Take, for example, China Pettway’s Bricklayer quilt (fig. 2). Within a gallery space, one can easily read the work as a nonrepresentational composition, enhanced by its bold use of color and rectilinear shapes, and understand how its formal elements recall the Color Field painting of artists like Mark Rothko. And yet that would only be a surface-level read of the material’s deeper memory, for that same nonfigurative work holds the stories of Pettway’s son and daughter and their playful fights about which side of the quilt was the best. The cloth holds that memory. Similarly, the corduroy fabric used in the quilt’s construction retains the cultural and historical legacy of the 1972 Sears and Roebuck contract with the Freedom Quilting Bee that employed Pettway’s mother in addition to countless women in the Bend. Quilts and textiles have embodied meaning in this way. As Lisa Gail Collins notes in Stitching Love and Loss, the textiles have testimonies.4 So, while museums consider inducting Black women quilters into the canon of abstract art, the depth, struggle, and resilience embedded in these fabrics must come with them.