From Kit or from Kin: Pattern Intersections in African American Quilts

Destinee Filmore

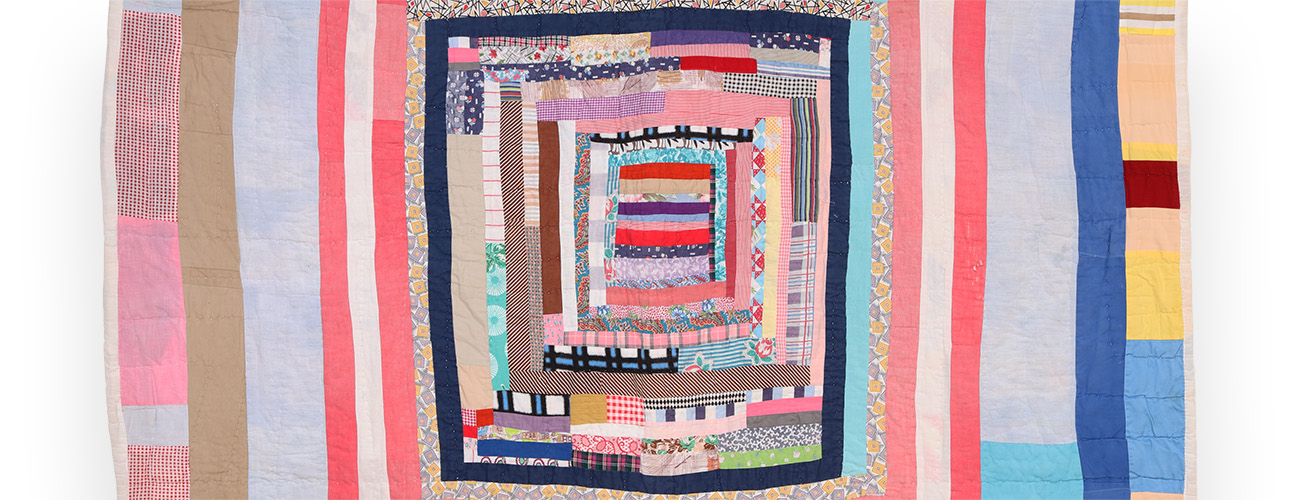

Maker once known, purchased in Alabama, Housetop Quilt with Multiple Borders (detail), 1940s, cotton, 86 × 67 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase through funds provided by patrons of Collectors Evening 2017, 2017.183.

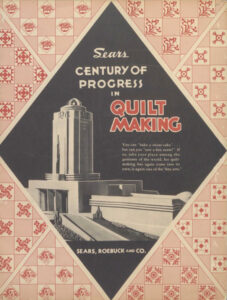

When readers opened the 1934 Sears, Roebuck and Co. catalog, Sears: Century of Progress in Quilt Making, they were greeted by the following: “You can ‘bake a sweet cake’ . . . but can you ‘sew a fine seam?’ If so, take your place among the geniuses of the world, for quilt making has again come into its own, is again one of the ‘fine arts’” (fig. 1). This triumphant proclamation was followed by a series of brief articles—one recounting the five million visitors to the Sears quilt exposition at the Century of Progress fair in Chicago the year before and another chronicling the democratization of quilts as they became a necessity for early American settler colonists. These articles eventually led to the content a subscriber likely found most important: quilting patterns. Ranging in price from ten to twenty-five cents and taking the form of perforated blocks, pattern pieces, and stencil diagrams, the offerings within the catalog’s pages were bountiful and made more attractive with red captions that detailed how many prizewinning quilts had resulted from each pattern. Sears and many of its competitors had taken to distributing quilt kits (which included the pattern and, for an additional fee, the materials required to complete a piece) through catalogs since the 1920s, though magazines marketed toward women had been publishing quilt patterns and instructions since at least the 1830s.1

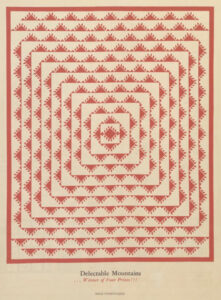

As I leafed through the Century of Progress catalog, I came across a pattern known as Delectable Mountains (fig. 2).2 This four-time-prizewinning pattern felt strikingly familiar even though I had never encountered it before. Designed by the wife of a New Jersey minister and distributed to subscribers across the country, the Delectable Mountains pattern (and the quilt from which it is derived) is one with little to no documented connection to the rural Southern United States. Yet I soon realized that its concentric bands radiating from within its center reminded me of the Housetop quilts that the quilters of Gee’s Bend were best known for making. As I read the succinct description of the quilt, I learned that its “greatest charm” was in the perfectly symmetrical form that required great care and precision to execute. The emphasis placed on technical precision and symmetry, and the way these qualities were presented as a prerequisite for aesthetic achievement, poses an interesting question: could the asymmetrical, improvisational, and often perfectly imperfect form of African American quilts be interpreted as a modernist progression of this form? Put in other terms, could the adaptation of existing quilt patterns or forms in African American quilts be seen as a radical revision on previous artistic modalities, which is the kind of innovation that we typically associate with abstraction? Perhaps a more engaging inquiry is one that considers an alternative approach to thinking about the relationship of Black quilters to pattern-based quilting traditions and how existing practices that may seem removed from patterning as a methodology might have a direct relationship to that practice. In other words, how have Black quilters engaged with, riffed on, or created quilt patterns? To answer this question, we must explore the historical contexts that distinguish two approaches to quilting: the infrastructure for circulating kits or patterns throughout the United States and the perceivable aesthetic differences and similarities between quilts made from kits or patterns and those made without them.

In the vernacular tradition of African American quilt making, improvisation and the use of scrap materials are ubiquitous and often associated with a lack of material surplus or knowledge of existing quilt patterns. Though they have become increasingly admired by different parties within the more mainstream art world, quilts made by African American artists have often been perceived as lacking in engagement with traditional (read: documented) approaches to quilt making. As opposed to using decorative appliqués or floral pieced patterns, the quilts produced by Black women in places like Gee’s Bend, Alabama, in the early twentieth century are often made using pieces of textiles to create geometric compositions. One of the most pervasive patterns used by makers based in Southern rural communities is the Housetop. As described by the Souls Grown Deep Foundation, Housetop quilts can be understood thusly:

Conceived broadly, the “Housetop” is an attitude, an approach toward form and construction. It begins with a medallion of solid cloth, or one of an endless number of pieced motifs, to anchor the quilt. After that, “Housetops” share the technique of joining rectangular strips of cloth so that the end of a strip’s long side connects to one short side of a neighboring strip, eventually forming a kind of frame surrounding the central patch; increasingly larger frames or borders are added until a block is declared complete.3

Understanding the Housetop approach as a form of patterning birthed from necessity yet maintained due to its efficiency and capacity for creative expression might encourage us to see the adherence to this form as its own type of technical and artistic triumph. The beauty of Housetop quilts lies in their tenuous balance of colors, strip width, and scale.4 Nevertheless, this assumption that African American quilt makers—especially those in the rural South—were disengaged from popular patterns or block pieces is an indicator of the temporality of materials (or limited distribution of pattern books) and a reminder that reliance on traditional archival sources for information is inherently flawed. While visiting Boykin, Alabama, for the second annual Airing of the Quilts Festival, I asked the artist Louisiana Bendolph if she recalled using or seeing others use quilt patterns when working. She had not. In her memory, older, more experienced quilt makers would teach their younger counterparts a set of patch patterns that would later become the building blocks for more complicated compositions.

Although Bendolph couldn’t recollect the use of officially named or published patterns, it is possible that her predecessors saw or engaged with them when purchasing scrap fabric from textile manufacturers, in catalogs, or in magazines and newspapers that were more readily available after the inception of the Rural Free Delivery (RFD) program (fig. 3). Started in 1890 to serve the forty-one million people living in rural areas who had limited access to mail delivery, the RFD provided unprecedented access to mail-based commerce, like catalogs and mail order, to thousands of communities across the country.5 Because of this revolutionary advancement, it is not inconceivable that an individual or group in a community like Gee’s Bend would have placed an order for a catalog of quilt patterns to learn from and use for their own creative practices.

Of course, purchasing a pattern book wasn’t the only means of encountering patterns; quilters might have come across them at local libraries or community centers or in school. As Lucy T. Pettway recalls in Gee’s Bend: The Women and Their Quilts, people might have also encountered patterns while working as domestic laborers: “My Aunt Lucy, my grandmother’s sister, she was working for the white people across the river in Camden. She give us a book the white people gave her with quilt patterns in it. My mother made some quilts after the book patterns and I do the same sometime—‘Stars,’ ‘Monkey Wrench,’ that’s about it.”6 The quilts that Lucy and her family members made from the pattern book would’ve been publicly visible to other community members as they swayed on clotheslines or hung from fences to air out from storage. Walking down the rows of quilts hanging in their neighbors’ yards, these practitioners would encounter new approaches or ideas and request instructions on how to make the blocks for themselves. The younger Lucy said as much: “I mostly made string quilts. I get my ideas different kind of ways. I used to pass by quilts out on a line, get me a piece of paper and draw a pattern from it, make me my quilt.”7 Lucy’s recollection confirms that rural quilting communities and their practices are catalysts for creative evolution and the transfer of knowledge.

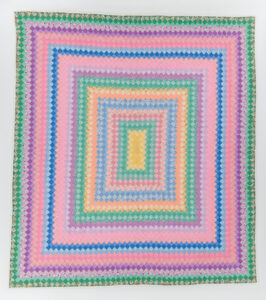

The way patterns are crafted and circulated in these communities might be one explanation for the formal resonances between named, mainstream quilt patterns found in books or catalogs and vernacular African American quilts. A comparison that most aptly represents the visual evidence for this theory is one between an untitled Housetop quilt made by an unidentified Alabama artist in the 1940s (fig. 4) and a Trip around the World quilt likely made in Ohio by an unidentified maker in the 1930s or 1940s (fig. 5). The proximity of their estimated creation dates is one of many similarities that the quilts share. Housetop Quilt with Multiple Borders and Trip around the World both use a bright color palette that includes vibrant swathes of blues, pinks, and greens in various shades. The inner medallion of Housetop Quilt is punctuated by a bold pink border made of fabric patches close enough in color that the lines of demarcation between them are almost imperceptible from a distance. This tripled border with a striking white interior surrounds the center medallion of the quilt and is the portion of the work’s composition that looks most like Trip around the World. Although a dozen patterned fabric strips in Housetop Quilt create the concentric bands around the initial horizontal block (instead of the same fabric for each band as seen in its counterpart), the overall structure of the interior echoes the exacting precision of that in Trip around the World.

One of the most apparent contrasts between the two quilts, which we might also read as a reflection of the differences between the two makers, is the use of fabric. In Trip around the World, each radiating band is composed of square diamonds made from the same material. Each line is a continuous, precise addition to the one before, and as they stack on top of one another, the shape of the quilt becomes a nearly perfect rectangle. In this regard, the advantages of working from a quilt kit are clear: uniformity to an almost manufactured degree is possible when the exact measurements and materials needed to construct a quilt are available. The curving lines evident in the outermost borders of Housetop Quilt, which provide a good amount of its character, enunciate the material conditions that the artist may have experienced. This was not a quilt solely made for the pleasure of making or with aspirations of winning a prize; this was a quilt made to keep its maker and their loved ones covered and warm using what was on hand.8 In the case of Housetop Quilt, we perhaps see a snippet of someone’s favorite dress or discarded scraps rescued from a local business. Certainly, we see an object that, though made for use, adheres to the aesthetic interests or vision of an individual. In this regard, the two quilts are united.

While the person who crafted Trip around the World may have been working from a published pattern that their Alabaman counterpart was potentially unaware of, both artists created utilitarian objects that we now regard as works of art. Each quilt reflects the material conditions of its production—one from calculated abundance and the other from scrappy resilience—and a shared interest in radiating designs that rely on balance and harmonization. To our knowledge, the maker of Housetop Quilt was not working from a published, mainstream pattern but was invoking a remembered pattern, one that was passed down to them from a family or community member who had learned it in a similar manner. By expanding our understanding of patterned quilts to include those created within rural communities where reference to mainstream quilting patterns could have existed at one remove, and by recalling one of the roles of enslaved women as producers of domestic quilts for their enslavers, we can begin to see them anew. In doing so, we could interpret Housetop quilts as abstracted or improvisational riffs on patterns like Trip around the World, Postage Stamp, or Grandma’s Dream.

In the act of recollecting and repeating the process of creating a Housetop quilt, the artists and makers who produce them engage in a patterning process that is replicable yet inherently unique to each individual. The capacity of this form is endless, and its ability to transform, expand, contract, repeat, skip, and more is a testament to its utility as an abstract expression of creativity. Each quilter must start from the same place—a medallion, an anchor—yet the journey that they embark upon to create the frame that grows from its center will always differ. Strip by strip, seam by seam, and frame by frame, the true essence of a Housetop quilt emerges: we are left with and enveloped by something beautiful to behold, a quilt that might not have won a prize at the Century of Progress fair but nonetheless evidences a parallel form of artistic excellence and which may have intersected with pattern knowledge more than we have previously considered.