Marsha MacDowell

How can quilts made by Black women change the way we tell the history of abstract art?

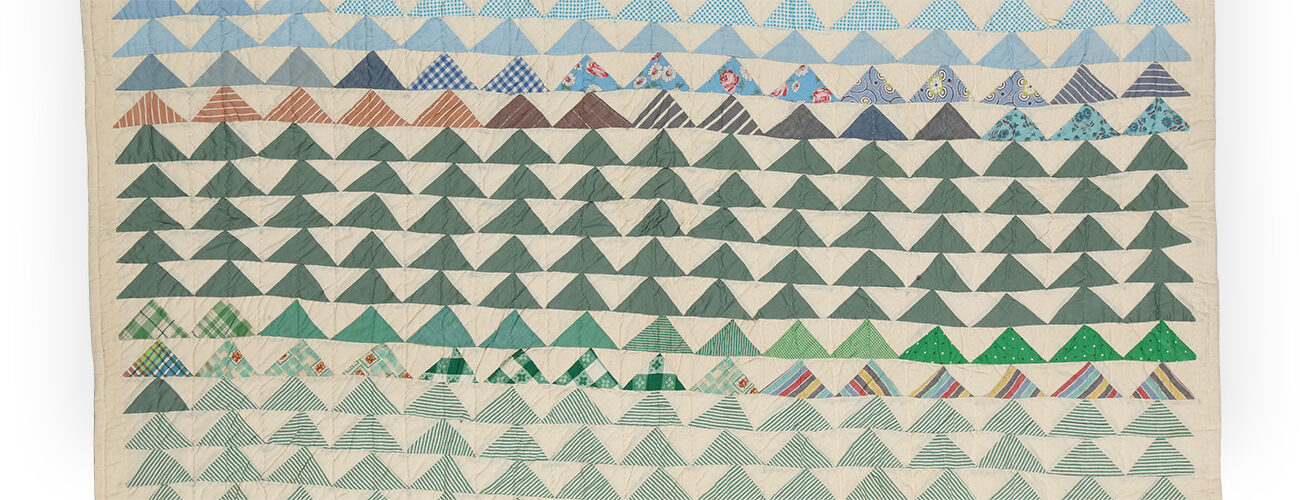

Maker once known, purchased in Texas, Directional Triangles (detail), 1940s, cotton, 80 × 64 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, gift of Corrine Riley on the occasion of Collectors Evening 2017, 2017.185.

In his seminal work on the material folk culture of the eastern United States, my friend and eminent folklorist Henry Glassie spoke of his dedication “to discover patterns where patterns are unclear and may not exist (the line between pattern and oversimplification is a fine one).”1 Over thirty years later, speaking of tradition and innovation in Swedish folk art, he observed that “the creative act is made comprehensible, the repetitive is distinguished from the inventive, by comparing things to one another in the context of culture.”2 In the High Museum of Art’s collection of quilts made by African Americans, the viewer can easily see the artists’ use of repetitive patterning as well as design innovations and inventions.

It is not just through the visual qualities of the textiles that quilts can communicate patterning and abstracted designs. The textiles also embed rich stories of individual and shared community life experiences, dreams, and ideas. Through hearing and understanding the stories associated with the making and use of the quilts, one can grasp the ways in which artists use their creative work to support and sustain themselves, their families, and their communities. Quilt artists often provide visual abstractions of oftentimes deep, complex narratives in their work through bits of color, embellishments, graphic and figurative designs, and fabric choices. Unpacking those shorthand textile texts, and therefore gaining a more complete understanding of the art, demands recording and making accessible the accompanying narratives. The efforts of the High and the Quilt Index’s Black Diaspora Quilt History Project are beginning to address those needs.3

Numerous art historians and critics have likened folk art in general and quilts in particular, especially the quilts made by the women of Gee’s Bend, to the work of artists who live and work in more urban spaces and whose work is intended to circulate in a commercial art market.4 They refer to some of these quilts as parallel works of art that mimic the work of contemporary architects, sculptors, and painters. Collections of diverse examples of work by African American quilt artists, such as the ones at the High, provide opportunities to examine such questions as the origins and distribution of design sources; how art historians, folklorists, and scholars in other disciplines have influenced the understanding of creative practices; what is intentional or unintentional in design decisions; the fluidity between considerations of craft and art; and the impact of marketing and art criticism on the repetition of pattern or abstraction in design.