O.V. Brantley

How can quilts made by Black women change the way we tell the history of abstract art?

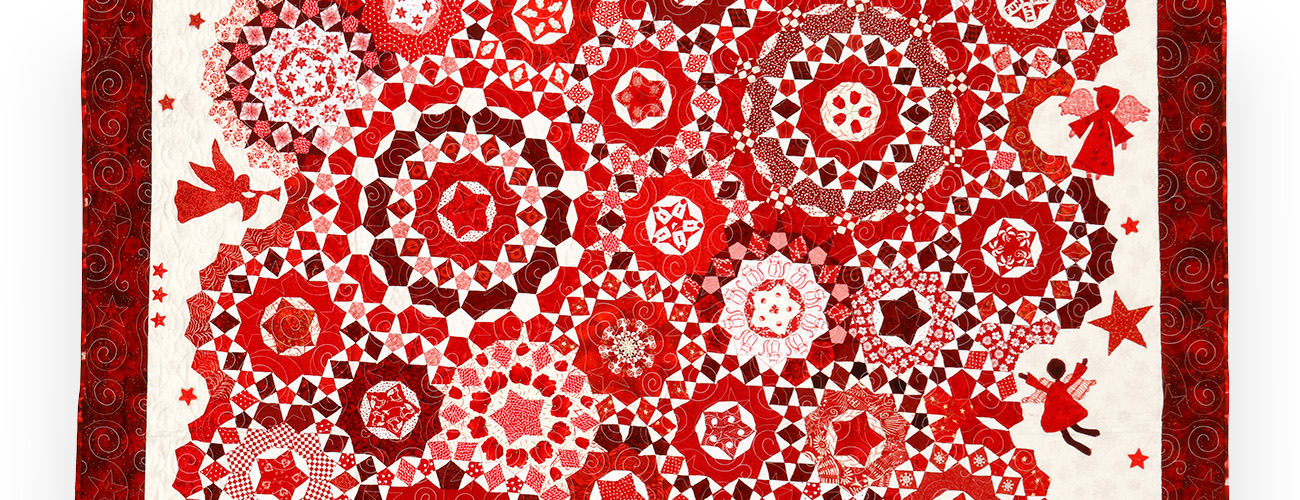

O.V. Brantley (American, born 1954), A Star Among Stars (detail), 2017–2020, cotton, fabric, buttons, 75 × 85 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from Black Quilts and Contemporary Art Centennial Initiative, 2024.35. © O.V. Brantley.

For sixteen years as cofounder of the Atlanta Quilt Festival, I have had a bird’s-eye view of quilts made by African American quilters to discuss, categorize, appreciate, and understand them. The Atlanta Quilt Festival, the largest African American quilt festival in the country, allows visitors to vote for Best of Show, which provides empirical data as to what our audience considers a beautiful quilt. More importantly, since my home is one of the drop-off points for the quilts that exhibit at the festival, I have had the honor and the joy of talking to quilters about their quilts. I have learned that no matter the technique, design, or category of the quilt, African American quilters are inspired to quilt because they have a story to tell.

I am the granddaughter of Clara Ford. Big Mama (as we called her) was born in Crossett, Arkansas, on December 12, 1892, and lived there until her death on May 20, 1966. She was a quilter, and I inherited eight of her quilts. I have early memories of her large quilt frame taking up almost the entire room in her small house.

Big Mama’s quilts are illustrative of many of the quilts made by African American women of her era (fig. 1). The Gee’s Bend quilts validated what was intended to be a utilitarian item as art and inspired a collecting frenzy. Exhibitions featuring these quilts are everywhere. Books have been written and licensing deals have been struck. The book Bold Expressions is especially eye-opening to me because when I viewed the quilts in the book, I felt I had seen them all before—although Big Mama’s quilts are not in the book.1

No doubt Big Mama’s quilts were inspired by the quilt blocks she saw around her. Forced to work with what she had on hand, her creativity sprouted.

What is one to do with only a small piece of one fabric that doesn’t match the other fabric? If it’s going on the bed to keep someone warm, does it matter?

What is one to do if the blocks don’t line up? Maybe a different block or an extra piece of fabric will work.

What is one to do if winter is coming and the quilt is not finished? Use big, random stitches to finish quicker and throw it on the bed.

Happily, in 2024, the style and creativity of early African American quilters is generally accepted as art, although these makers were inspired by well-known quilt patterns. For example, the Sunbonnet Sue, pin wheels, and a lot of half-square triangles are present in Big Mama’s quilts. I believe, though, that we must dig deeper to properly understand this newly discovered and validated art form. We must seek the story.

African American history is grounded in being unseen and unheard. As enslaved people, African Americans could only speak to white people when spoken to and then only while looking at the ground. There was a time when it was illegal for an enslaved person to read and write. As household help, they were viewed as invisible while standing and serving in plain view. It is only natural that such a history would inspire storytelling in the creative process.

Big Mama loved red, as seen in her quilts, and so do I. Red is a “look at me” color. It screams, “I am here.” So, color choice is part of the creativity of the quilts. The quilts have more to say, though. Many African American quilts of Big Mama’s era are memory quilts. They may include pieces of a child’s Easter dress or a husband’s worn-out work clothes or a tattered house coat.

We may not know the whole story when we look at a quilt, but it is there. What was Big Mama thinking when she used such strange color combinations and placed her patches in such a haphazard way? We may never know, but it is the story—her story and only her story—that makes her quilts unique. While we observe the creative beauty, we must honor the story.

My quilt A Star Among Stars (fig. 2) tells my story on many levels.2 Born in a small town in Arkansas in 1954 during the Jim Crow era, I did not attend integrated schools until I was in the seventh grade. Discipline and fortitude took me to college, law school, and a high-profile legal career. Proving I was “just as good as” (or better) is a large part of my life. Naturally, my life experiences influence my quilt making, and most of my quilts are somewhat autobiographical.

So, what is the story I want to tell you in A Star Among Stars?

First, the pattern is complex and uses the English Paper Piecing technique, one that most African American quilters would not normally choose to tackle. Creating A Star Among Stars required tirelessly piecing approximately three thousand small geometric shapes by hand with a precision that allows all the pieces to fit together. Destroying racial stereotypes is part of my story.

A Star Among Stars required discipline and fortitude. It took me approximately three years to make it, and there were many days when I wanted to trash it and move on. I did not, as I know that discipline makes me successful.

Stars have long been a symbol of excellence, and there are many stars pieced into the fabric of A Star Among Stars and added as buttons. I strive to be a star when tackling important tasks.

Angels surround the center of A Star Among Stars because I believe in angels, both heavenly and earthly. I believe my angels are always with me, encouraging me when I want to stop and rejoicing when I succeed. My angels are in on the story and always have been.