Past, Present, Future: Black Quilts at the High Museum of Art

Katherine Jentleson

Annie Mae Young (American, 1928–2013), “Lazy Gal” Work-Clothes Quilt (detail), 2002, cotton, 95 × 72 inches, High Museum of Art, Atlanta, purchase with funds from Peggy, Margaret, and Mary Rawson Foreman and gift of the artist and the Tinwood Alliance in honor of Rawson Foreman, 2005.304. © Annie Mae Young.

Since the 1980s, Black quilts have had a steady—if scarce—presence at the High Museum of Art across many of the museum’s collecting areas, though this has grown substantially in recent years. On the occasion of the opening of Patterns in Abstraction: Black Quilts from the High’s Collection, the museum is publishing a new suite of resources on this growing area of its collection, which has more than quintupled since 2017. This introductory essay seeks to both give an overview of these projects and chronicle where the museum has been, where it is now, and where it seeks to go regarding this quintessential artistic tradition and its increasingly recognizable impact on generations of artists working in textile-based media and beyond.

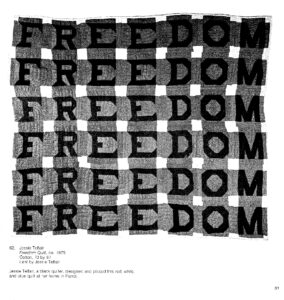

The High began collecting Black quilts in the Decorative Arts and Design department in 1982 with Jessie Telfair’s iconic Freedom quilt (Plate 1), a version of the activist statement piece that Telfair made after being fired from her job as a cafeteria cook in Parrott, Georgia, for registering to vote in the 1964 general election (fig. 1).1 In the mid-1990s, Decorative Arts and Design also acquired two important historical examples, a Bible scenes quilt (Plate 2) handed down in the Drake family of Thomaston, Georgia, and a Snake quilt (Plate 3) from North Carolina. That department has continued to collect objects of excellence with the 2020 acquisition of an important Tennessee Valley Authority quilt (Plate 4) designed by Ruth Clement Bond, a Kentucky-native whose The New York Times obituary credited her with transforming “the American quilt from a utilitarian bedcovering into a work of avant-garde social commentary.”2 The Modern and Contemporary Art department also made important quilt acquisitions in the 1980s and 1990s, accessioning in 1988 Faith Ringgold’s Church Picnic (Plate 5), which is part of the Story Quilts body of work that she began in 1983, followed by Sonny’s Bridge (Plate 6), a tribute to her childhood friend jazz musician Walter Theodore “Sonny” Rollins that was featured on the cover of The New Yorker following Ringgold’s recent passing.3 Ringgold’s fusion of paint and cloth went on to inspire many artists who were formally trained in multiple media and decided to return to sewing practices that had been in their families for generations, including Bisa Butler and Dawn Williams Boyd, whose quilts have also recently entered the museum’s Modern and Contemporary collection.4 The African Art department, meanwhile, includes examples of textile practices such as kente weaving and adire dyeing, which scholars like Robert Farris Thompson and Maude Southwell Wahlman suggest inspired some of the distinct aesthetics of abstract, improvisational quilting that flourished in the Black South and its Great Migration diaspora.5 Possibilities of transatlantic exchange are the basis for Nigerian artist Nike Davies-Okundaye’s recent body of work that combines vintage adire textiles in compositions that model improvisational quilts, which may soon become part of the African Art department’s plans to amplify the presence of Nigerian modern and contemporary artists. Even the High’s Photography department has important material related to quilts, including a photograph by Doris Derby, a photographer and activist who focused her lens on the women of the Civil Rights Movement, including participants in a quilting bee in Aberdeen, Mississippi.

Founded in 1994, the Folk and Self-Taught Art department did not begin collecting quilts until more than a decade later. In 2006, the museum became part of the national tour of The Quilts of Gee’s Bend, an exhibition that opened at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in 2002. When it was presented at the Whitney Museum of American Art that same year, The New York Times critic Michael Kimmelman called it the most “ebullient art show of the New York season” and proclaimed the sixty quilts on view “some of the most miraculous works of modern art America has produced” (fig. 2).6 As the High prepared to present the show, it acquired four quilts by Irene Williams (Plate 7), Annie Mae Young (Plate 8), Mary Lee Bendolph (Plate 9), and Bendolph’s daughter in law, Louisiana Bendolph (Plate 10), that span many of the variations for which Gee’s Bend is most celebrated, including Housetop, Strip, and Work Clothes quilts. In 2017, the museum acquired eleven additional Gee’s Bend quilts as part of its Souls Grown Deep acquisition, including several works that were in The Quilts of Gee’s Bend, like Arcola Pettway’s Lazy Gal variation (Plate 11), which bears a striking resemblance to an American flag.

Given the possibility for collecting quilts across so many departments, several of which uniquely focus on objects and artists that are often marginalized in mainstream histories of art, one would expect the High to have a much larger quilt collection than it does. Yet the museum did not collect any quilts between 2005 and 2017. This lack is all the more surprising when one considers how Black quilters flourished in these years, in the succession of Gee’s Bend exhibitions that followed the 2002 show and through increased opportunities for exhibitions through the Women of Color Quilter’s Network (WCQN), which Dr. Carolyn Mazloomi founded in 1985 and today includes more than fifteen hundred members.7 Here in Atlanta, quilters O.V. Brantley, Aleathia Chisholm, and Marva M. Swanson founded the Atlanta Quilt Festival (AQF) in 2014, the only regional quilt festival dedicated to supporting African American quilters.

One reason for the stagnation of the High’s collection of textiles—made by any artist regardless of race—is that until 2017, the museum did not attract or pursue any major textile collections.8 When I joined the museum as Merrie and Dan Boone Curator of Folk and Self-Taught Art in late 2015, the small number of Black quilts in the collection came as a surprise and quickly became a collecting priority for me. The High will never have the largest collection of Black quilts, but in 2017 it invested in groups of quilts from the Souls Grown Deep Foundation and West Coast collector and textile artist Corrine Riley. These acquisitions enabled enough depth in the collection that, beginning with the 2018 reinstallation of the museum’s collection, there are now always a number of Black quilts on view in the Folk and Self-Taught Art galleries, often in dialogue with historic quilts from the Decorative Arts and Design department and textiles from the African Art department as well as thematically inspired juxtapositions with contemporary art by Radcliffe Bailey and Roger Brown and photographs from our renowned civil rights collection (fig. 3).9

This increased presence seemed to be noted by the Brown Sugar Stitchers Quilt Guild (BSSQG), an Atlanta-based guild that celebrated its twentieth anniversary in 2020 and invited me to one of its virtual meetings during the height of COVID-19 confinement. The following year, BSSQG member Carolyn White, after seeing on the local news that the museum would be a venue for the touring Obama Portraits show, sent an email to one of the museum’s general addresses wanting to share a related quilt she had made that won Best in Show at the Atlanta Quilt Festival in 2021: Awestruck before an Unforgettable Nubian Queen, or From Gee’s Bend to Royalty (Plate 12). When I paid White a visit, I was absolutely astounded by the vigor of the quilt and its many layers of meaning, including how it originated as a response to a BSSQG member challenge to pay homage to African American quilters of the past. The museum purchased the quilt and has continued to support the work of stellar Atlanta-based quilters, including Marquetta B. Johnson, a long-time High teaching artist and nationally renowned innovator of hand-dyed fabric, and O.V. Brantley, a retired high-powered lawyer who channeled her passion for excellence and leadership skills into her technically challenging quilts and founding of AQF. As many of the quilters represented in the High’s collection are deceased or unnamed, supporting the work of living quilters, including the many world-class practitioners here in Atlanta, has become an important dimension of the High’s present and future acquisition of Black quilts.

Another direction that this collecting initiative has taken concerns the legacy of Black quilts for twentieth- and twenty-first-century artists—both those who are formally trained in various media and come back to quilts and those who are self-taught but also impacted by the quilters in their lives. In recent years, the museum has acquired works by Thornton Dial (Mrs. Bendolph), Lonnie Holley (Shadows of the People), and Ronald Lockett (Untitled, from the Oklahoma series) that all pay homage to quilters whose aesthetics and care practices shaped their experiences and art. As I worked on the 2021 exhibition Really Free: The Radical Art of Nellie Mae Rowe, I came to appreciate how Rowe pieced her drawn compositions like a quilt. Her mother was an accomplished seamstress who taught Rowe to sew her own clothes as well as the dolls she would make both as a child and in adulthood, and this past spring, I had the opportunity to see the only quilts that Rowe made that are known to have survived. During the years I was pursuing these projects, I was also becoming more familiar with more work by trained African American artists who had brought quilt legacies into their artistic practice in the postwar period. For instance, as the coordinating curator for the High’s presentation of Outliers and American Vanguard Art, which included a gallery on textile and textile-adjacent practices, I became familiar with the work of Al Loving, an artist who sewed strips of torn and painted canvas together, often with the help of his wife, who was a seamstress (fig. 4). A year later, my former colleague Stephanie Mayer Heydt curated a show on Romare Bearden for the museum, which reminded me of what an important influence quilting was on his innovations in collage. In effect, I felt that I was seeing the phrase “My mother was a quilter” again and again in the accounts of Black artists of the twentieth century, often regardless of their level of formal training.

The turn toward textiles was becoming highly visible in contemporary art as well: Bisa Butler’s breakthrough show opened at the Art Institute of Chicago in 2020 while Sanford Biggers’s Codeswitch was also touring the country. This renaissance has continued to blossom with Legacy Russell’s The New Bend, which showed at various Hauser and Wirth locations beginning in 2022; the Columbus Museum of Art’s 2023–2024 Quilting a Future; and Cecelia Alemani’s 2023 women-focused exhibition at the Shah Garg Foundation that featured work by Emma Amos, Elizabeth Talford Scott, and her daughter Joyce Scott, who were both subjects of major exhibitions at the Baltimore Museum of Art this year. In London, the Barbican Centre opened Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art in February 2024, which will travel to subsequent venues after it closes there in May. And here in Atlanta since spring 2023, there has been Threaded at the Spelman College Museum of Art and Coulter Fussell’s solo exhibition at Atlanta Contemporary.

Black Quilts and Contemporary Art Centennial Collecting Initiative

This abundance of attention to quilts by contemporary artists—many of them of African descent—led me to propose to my curatorial colleagues and museum leadership that the High embrace this zeitgeist with a Black Quilts and Contemporary Art Collecting Initiative that would be part of a larger transformation of the museum’s collection in advance of its centennial anniversary in 2026. This initiative not only funds the continued purchases of work by “traditional” quilters who are not formally trained but also those of artists who are and who look to legacies of Black quilting as inspiration in their practice. Our first purchases included Bisa Butler’s Colored Entrance (after Department Store, Mobile, Alabama) (Plate 13), a stunning quilt showing Butler’s signature attention to detail and symbolic use of Dutch wax fabrics and spotlighting Joanne Wilson and her niece in front of a department store in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1956. Wilson was part of the family that Gordon Parks photographed when LIFE Magazine sent him to document segregation in the South. In addition to exemplifying Butler’s practice of connecting with and revivifying subjects from archival photographs and other print media, this quilt connects beautifully to the museum’s leading civil rights photography collection, which includes twelve works from Parks’s Segregation Series, including his photograph of Wilson. Reflecting on what drew her to reinterpret this photograph while she was a fellow at the Gordon Parks Foundation, Butler said, “Through his eyes I saw beauty, delicacy, loyalty, intelligence, and strength. He depicted women the way I see them, with reverence and respect. His photograph surged me to try to do the same. [. . .] African American women and mothers deserve to be seen, heard, paid, and protected. They must be thanked and acknowledged for all they have done and continue to do. We need Black women.”10

The High has also acquired two works by the Atlanta-based artist Dawn Williams Boyd, who uses textiles as a soft landing for difficult topics, such as the secretive, behind closed doors, political deliberations that exemplify the opacity of United States governance in Smoke-Filled Rooms (Plate 14) and the Atlanta Child Murders of 1979–1981 in These Bones (Plate 15). Like Butler, Boyd earned a Bachelor of Fine Arts and has worked in multiple media but for more than a decade has primarily embraced sewing, a practice that she has known since childhood thanks to family elders who sewed. She refers to her works as cloth paintings, a choice that both challenges the stigma that quilts are less than painting and underscores the truly painterly surfaces of her fabric canvases, which feature sumptuous layers of cloth that draw the viewer close and exist in tension with the often difficult imagery of her work. As trained American artists living and working today, Boyd’s and Butler’s works are formally accessioned to the Modern and Contemporary Art department, also contributing to my colleague Michael Rooks’s efforts to amplify representations of women of color in that collection as the museum moves toward its centennial. My colleague Lauren Tate Baeza, curator of African Art, meanwhile has been working on her own centennial initiative around African modernism, which includes amplifying the presence of Nigerian art—already a collection strength at the High but one that has too often focused on traditional modes of expression rather than the modernist art movements that blossomed in Lagos at the hands of artists like Bruce Onobrokpeya. Her interest in an adire quilt by Nike Davies-Okundaye, as well as the Folk and Self-Taught Art department’s acquisition at the 2023 Collectors Evening of an important early voudou flag by Haitian artist Myrlande Constant, demonstrates how this textile initiative is not focused solely on African American artists but is indeed inclusive of Black artists in a global sense.

One of the other reasons that Black quilts may have had a less robust presence at the High in the past is that they could be accessioned in so many areas that no department felt singularly responsible for them. This initiative recognizes how some media-based practices challenge classification and require cross-departmental collaboration in order to make sure they are more fully accounted for. Guiding the various cross-departmental acquisitions that this initiative achieves is the understanding that textile-based work has always had many homes at the High, and the museum will be flexible and collaborative about where a work is accessioned. Departmental classification is both a formality that does not reflect limitations on the kinds of dialogues an object can have across the collection and also a designation that must be considered critically: acknowledging formal training when we accession is essential, to recognize the full integrity of both credentialed and uncredentialed art practices, including the way that those engaged in the former sometimes count the latter as important artistic influences, without fully eliding the differences between the two.

Relatedly, in the years to come, I am planning a large exhibition that takes the flourishing of contemporary quilt practices as its endpoint but reaches back into the nineteenth century to chronicle the rich history of Black quilters like Elizabeth Hobbs Keckley (Mary Todd Lincoln’s seamstress) and the iconic Georgia quilter Harriet Powers. Attempting such a project would not be possible without the pioneering recovery and documentation of historical Black quilts by scholars like Gladys-Marie Fry, Cuesta Benberry, Dr. Carolyn Mazloomi, and Kyra E. Hicks. The exhibition will also look broadly at twentieth-century practices that show an aesthetic debt to the “mothercraft” of quilting like those of Bearden (fig. 5), Loving, Dial, Lockett, and Rowe mentioned earlier.11 But given the ambitious scope of such an exhibition and my own position as a White curator who strives for an ethical practice around the Black artists whose legacies it is my privilege to platform, I have been tempering my Virgo (Aries rising) spirit to plan and enact quickly. I am so grateful to the many people who have welcomed my interest in quilts and Black quilts specifically and become vital interlocutors and sources of inspiration, including Kyra E. Hicks, Roderick Kiracofe, Karen Cooper, Elaine Yau, Legacy Russell, Kim V. Kelly, Scott Browning, Raina Lampkins-Fielder, and the incredible group of scholars, quilters, and curators who came to the High for a convening in May 2023 (which was generously funded by the Terra Foundation for American Art as part of its support of the exhibition Patterns in Abstraction: Black Quilts from the High’s Collection that this publication accompanies). Featuring seventeen quilts acquired since 2005 and on view at the High from June 28, 2024, to January 5, 2025, Patterns in Abstraction asks, “How can quilts made by Black women change the way we tell the history of abstract art?”—a question that admittedly and intentionally pokes contentious histories of affinity-based comparisons and overly monolithic approaches to Black quilts that will be briefly limned here.

Quilts and Abstraction

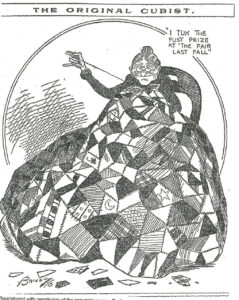

As most art history courses will teach, the 1913 Armory show was a bellwether moment for the transmission of abstract painting from the studios of White male European artists to the American audiences who gathered at New York City’s 69th Regiment Armory to experience it for the first time on a large scale. In the wake of its impact, cartoonists had a field day skewering the new nonrealistic styles on view, most famously taking aim at Marcel Duchamp’s controversial Cubist masterwork, Nude Descending the Staircase. One such response depicted an elder White quilter creating a Crazy Quilt—a tradition whose emergence is linked to Americans’ exposure to international practices at the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial, where the Japanese Pavilion showcased cloisonné enamelwork and where a display of elaborate embroidery from the Royal School of Needlework was also on view (fig. 6). Making the connection between the Crazy Quilt’s angular patchwork and the shards of Cubist painting, cartoonist Claire Briggs dubbed her quilter “The Original Cubist.”

The argument about quilt makers’ role in inventing abstraction was more boldly made in the 1971 exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art, Abstract Design in American Quilts, whose curators, Gail van der Hoof and Jonathan Holstein, proposed that “the powerful images we saw in many pieced quilts had preceded similar developments in modern abstract art, in some cases by a century or more.”12 The exhibition was a dramatic success, receiving rave reviews in The New York Times, going on to travel internationally, and even revived recently in a fiftieth-anniversary exhibition at the International Quilt Museum. Its premise and stunning reception also attracted backlash from those who were frustrated to see an art form with its own unique history appreciated only insofar as it could be compared to a paradigm of artistic innovation dominated by White men. Amelia Peck, a longtime curator of decorative arts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and a widely respected authority on quilts, offered such criticism: “From the beginning van der Hoof and Holstein had little interest in quilts as textiles, whether decorative or useful; to them, quilts had meaning and value only when they were equated with formal works of painting.”13

Neither did Abstract Design include any examples of quilts attributed to Black women, but the 1970s and the decades that followed would bring a flourishing of exhibitions, scholarship, and general awareness of the subject, largely at the hands of Black scholars and curators.14 In 1976, the catalogue for Missing Pieces: Georgia Folk Art 1770-1976 featured new research from Gladys-Marie Fry on Harriett Powers, the now-iconic matriarch of Bible Quilting, who was recently recognized with a new headstone and historic marker at her resting place in Athens, Georgia (fig. 7). In 1990, Fry published a text that recovers the histories of more than 120 quilts previously improperly or under attributed and has been reeditioned many times since.15 Three years later, Cuesta Benberry published a catalogue for the exhibition Always There: The African-American Presence in American Quilts, which chronicles a pluralistic vision of African American quilts rooted in rigorous research and documents the flourishing of different traditions of Black quilting from the nineteenth century through the last quarter of the twentieth century. Although Benberry embraces the brilliance of quilters working in improvisational styles, her archival and primary-source-based research reveals that Black quilters had worked in a wide range of styles because, as she put it, “There was a need to dispel certain myths that had developed about African American quilts [. . .] to portray the enormous diversity that characterized black-made quilts and, when possible, give voice to the quiltmakers themselves.”16 Roland Freeman, a photographer and folklorist who began collecting the quilts, portraits, and stories of Black quilters while working for the Mississippi Folk Life Project in the 1970s, shared this belief, leading him to publish the first major survey of Black quilts, A Communion of the Spirits: African-American Quilters, Preservers, and Their Stories, in 1996.17 Freeman’s quilt collection was recently gifted to the Mississippi Museum of Art and will be the subject of an exhibition, Of Salt and Spirit: Black Quilters in the American South, opening in November 2024 and curated by Dr. Sharbreon Plummer.

One of Freeman’s most well-known photographs is a portrait of Annie Mae Young standing with her granddaughter in front of a woodpile covered with several of her quilts, including a Work Clothes quilt that, just under two decades later, would become part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s collection (fig. 8). When Freeman published his book, Atlanta-based collector William S. Arnett had been at work for the better part of a decade documenting and collecting the visual art of the Black South after connecting with the Birmingham, Alabama-based artist Lonnie Holley, who led Arnett to Thornton Dial and his artistic clan—artists who proved Arnett’s theory that every culture with great music also has great visual art. Arnett went on to publish and organize dozens of exhibitions and related books on artists who became part of an emergent canon, starting with two major volumes titled Souls Grown Deep, a description derived from the last line of a Langston Hughes poem: “My soul has grown deep like the rivers.”18 After Arnett saw Freeman’s photograph of Young and her quilt, he turned his attention to Young’s community of Gee’s Bend, a remote part of Boykin, Alabama, that had been more isolated than other parts of Wilcox County because of its location in the “bend” of the Alabama River.

-

Figure 8. Roland Freeman’s 1993 portrait of Annie Mae Young, standing with her granddaughter Sharquetta, in front of quilts laid out on a wood pile.

-

Figure 9. Arthur Rothstein’s 1937 photograph of an unidentified quilter and her family sewing a quilt in Gee’s Bend, Alabama, 1937.

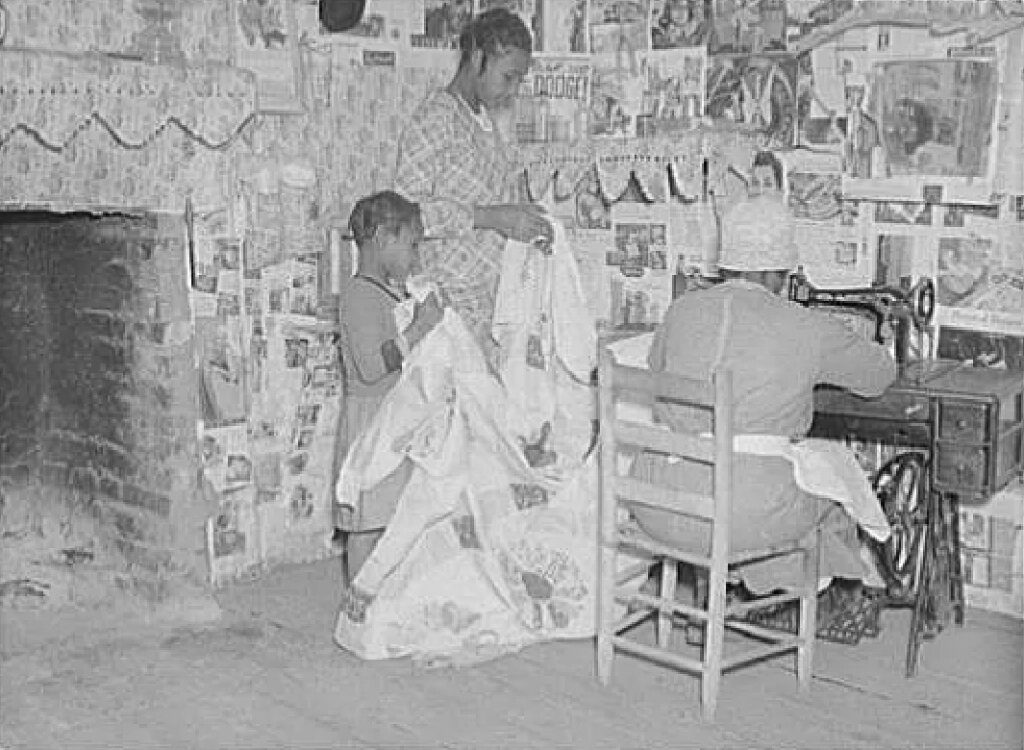

Arnett was far from the first White man to come to Gee’s Bend and be bowled over by the exceptional artistry of its quilters. The community was documented by Farm Security Administration photographers like Arthur Rothstein in the 1930s (fig. 9), and in 1966, minister Francis X. Walter returned to his native Alabama to run a branch of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Camden, the seat of Wilcox County, which was just across the river from Gee’s Bend. Walter quickly noted the exceptional quilts in the area and recognized how they could be sold in other, more urban markets like San Diego and New York City at a premium to raise money for the civil rights cause and to give Wilcox County residents the same weekly wages that they were earning through the area’s most-held occupation of domestic work. Within two months, dozens of quilters stepped forward for the cause and the new income-generating opportunity and, in April of 1966, ten of them added their names to articles of incorporation for the Freedom Quilting Bee.19 Six years later, the Bee started a contract with Sears, Roebuck and Co. to produce corduroy coverlets and shams—an important precursor to Target’s recent inclusion of Gee’s Bend in its Black History Month collection (fig. 10). The Target collaboration was a milestone for introducing the history of Gee’s Bend to the masses, but also a paradox, as Target’s business model thrives on the kinds of predatory, overseas labor practices that ultimately made the Freedom Quilting Bee unsustainable by the late 1980s.20 When Arnett arrived in the late 1990s, Gee’s Bend residents had all but ceased to make their livelihoods from quilts, with younger generations moving out of the Bend to find other economic opportunities.

Within six years of seeing Freeman’s photograph, Arnett acquired the Young quilt and hundreds of others and began working on a blitz of exhibitions and publications featuring Gee’s Bend quilts that started with the previously mentioned 2002 exhibition, The Quilts of Gee’s Bend at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston.21 Arnett and his collaborators, including Alvia J. Wardlaw, Bernard L. Herman, and my predecessor at the High, Joanne Cubbs, believed, like Freeman and Benberry, that documenting the quilters’ voices was essential; many of the publications, as well as the Souls Grown Deep Foundation’s website, offer vital accounts of the quilters. However, quilters more often spoke about (or were asked about) their lives in the Bend or generally about their approach to quilting than about specific quilts they made. In October 2023, I traveled to the Bend with a group of museum colleagues to interview the living Gee’s Bend quilters who have work in the museum’s collection and asked them questions about those quilts—interviews that yielded tremendous knowledge about the specificity of the fabrics used in their quilts, their intentionality in design, and their associated memories, which are available in the video library of this publication.

Moving the Dialogue Forward

Centering quilters’ own expressions about how they engage with the artistic and intellectual processes that have long been considered hallmarks of abstraction—such as distilling real-life phenomena into nonrepresentational compositions and color schemes, or transferring memories and experiences into the inert matter of the art object itself—is one way to better position quilts in relation to abstract art. But what about the thousands of quilts that were collected or passed down without quilters even being asked their names, let alone questions about process, materials, or intent, because the idea that such information could be culturally significant perhaps seemed impossible? Must we discount possibilities of artistic intent that can be considered more than decorative because of a lack of information due to systemic failures of valuing Black women in a society governed by patriarchy and racism? Scholars like Tiya Miles and Lisa Gail Collins, as well as the artist Sonya Clark, have masterfully demonstrated how not to give up on profoundly beautiful textiles that feel lost to history through methodologies that combine archival research, critical fabulation in the school of Saidiya Hartman, and subjective interventions.22 In the spirit of not giving up on compelling objects because attribution and provenance are lacking at present, Patterns in Abstraction includes both quilts for which we have or could get oral histories and those for which we could not but which were all variations on Birds in the Air and Housetop patterns. These patterns did not necessarily originate with Black quilters, but they were adopted and varied in often asymmetric and improvisational modes that further align them with practices of individualistic originality associated with abstraction. The tension between pattern knowledge and paradigms of individual genius present in improvisational quilts is something that Destinee Filmore explores in her essay on pattern circulation for this publication. These patterns and their variations became a point of focus for this exhibition not only because of the frequency with which they appear in quilts made in the Black South and its diaspora but also because they are rooted in the visible world. The repeating rows and columns of rectangular strips that flank the central medallion of a Housetop, for example, echo the stacked and layered boards of the hand-built structures that once dominated Gee’s Bend, like the “corncrib” seen in this photograph taken by an unnamed Farm Security Administrator photographer (fig. 11).

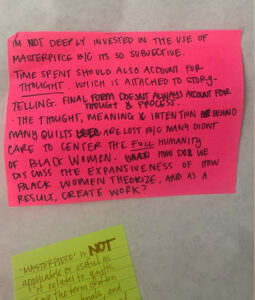

Previous scholarship has taken on the architectural aesthetics of Housetop quilts, most notably in the exhibition Gee’s Bend: The Architecture of the Quilt (2006), which included spread upon stunning spread of the right angles and color blocking still apparent across the architecture of Gee’s Bend today. Patterns in Abstraction’s return to the proposition that Housetop quilts are actual abstractions of the built environments they once served within is worthwhile because of how much more radically open to revising narratives of abstraction the art world is now than it was twenty years ago, when The Architecture of the Quilt circulated. Patterns in Abstraction also addresses the question of whether Black quilters can be better positioned within histories of abstract art with the understanding that there are many possible answers, including counter inquiries that might reject it outright. When asked in the space of our convening of about sixteen outside curators, scholars, and quilters in discussion with the museum’s curatorial and Learning and Civic Engagement colleagues, powerful questions emerged, including: “Does abstraction ‘allow’ quilts in on white terms?” In the context of the High, a museum that, like most, has been so fundamentally oriented around White terms, Patterns in Abstraction attempts to be a show that says, “yes, but.” “Yes,” it contends with, and therefore still assigns value to, established hierarchies of art that have historically privileged White men and been gatekept by White curators. “But” this publication and exhibition attempt a more multivocal approach to including the convening participants’ calls to “center the full humanity of Black women” (fig. 12) and to make room for “the expansiveness of how Black women theorize and create work.”23 In the months following the convening, all participants were invited to write short essays responding to the central question of the show, which are excerpted in the exhibition didactics and published in full here. In a range of registers that include polemical, optimistic, poetic, personal, and more, their voices form a patchwork that reflects the varied compositions of the quilts on view in Patterns in Abstraction.

The exhibition’s checklist also changed as a result of the convening, expanding from its original Birds in the Air and Housetop focus to include a group of quilts that might be considered abstract portraits of loved ones grown or passed, an idea inspired by Dr. Lisa Gail Collins’s book Stitching Love and Loss: A Gee’s Bend Quilt.24 I also decided to include quilts that are not distillations of geometric form and color at all but that show other forms of complex meaning, or as the quilter and AQF founder O.V. Brantley likes to say, a “story” beyond what is immediately seen. In fact, the exhibition begins with a Birds in the Air quilt by Lucy T. Pettway and the related aforementioned AQF Best in Show winner by Carolyn White. The realistically depicted subject matter of White’s quilt may be recognizable to many—a scene in front of Amy Sherald’s portrait of First Lady Michelle Obama that went viral in 2018. But White’s quilt contains many layers of meaning that are not initially seen, including a connection to the Pettway quilt that hangs beside it. As the layered title of her quilt, Awestruck before an Unforgettable Nubian Queen, or From Gee’s Bend to Royalty, suggests, White is also paying tribute to Gee’s Bend quilters like Pettway; she was aware of Sherald’s statement about her choice of First Lady Obama’s dress at the press conference where the Obama portraits were unveiled: “It has an abstract pattern that reminded me of the Dutch artist Piet Mondrian’s geometric paintings. But [. . .] also resembles the inspired quilt masterpieces made by the women of Gee’s Bend.”25 Sherald’s articulation of abstract art as belonging to both Black quilters and long-heralded White male innovators like Mondrian is a much-needed revision to traditional art historical narratives from which this show draws inspiration. Her vision and its reflection in White’s quilt are proof of how the disruption of narratives of abstraction has already happened—whether we as academics and curators feel fully comfortable with it—and has been happening for decades in the work of artists with expansive definitions of aesthetic innovation. So, we had better catch up.